From the moment Dhiru Thadani’s book, The Language of Towns & Cities: A Visual Dictionary landed on my desk, I have been enjoying it immensely and making use of it regularly. It really did ‘land’ there – all 804 pages and 8 pounds, 11.5 ounces of it. The book is nothing short of a life’s work, with robust contributions from some of the many accomplished practitioners, an inspiring forward by Leon Krier, and an introduction by Andres Duany. The lavish praise on the book by the 2011 David Lewis Lecturer is well deserved. So my question for my fellow practitioners is: Now what?

This book is very well organized for easy use. The ‘encyclopedic’ format allows it to serve as a quick research guide (paging through the index of Hegemann and Peets’ American Vitruvius is not a good use of time) with clear illustrations, photographs, and descriptions of towns and cities. Much like looking around Pittsburgh, this book contains a wealth of basic, practical, and even unexpected examples within a single book. The book is organized into 544 comprehensive entries that include: the fun: “Noise” and “Nostalgia”; the details: “Site Walls” and “Signage”; the practical: “Recycling” and “Roof Forms”; and the basics: “Regulating Plans” and “Rail Transit”. Beyond practice-based information, there is also historical information of some of our favorite people in the profession including Jefferson and Jacobs, and documentation of some of our favorite cities like Paris and Rome (what a nice reminder of my semester abroad!).

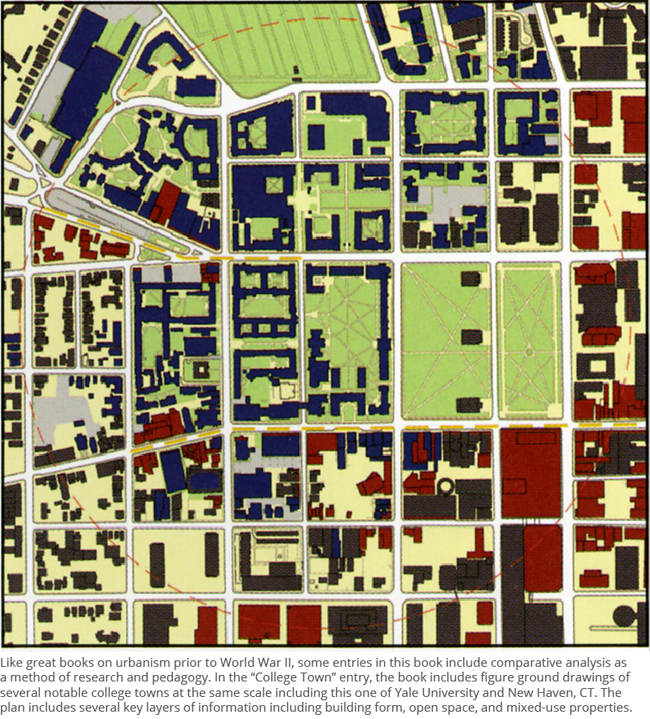

This book illustrates how the practice of urban design has matured in recent decades. Prior to World War II, there were many resource books of this typology. In the years following the war, symmetrical with a lack of interest in city-building, effective books on urbanism disappeared as well. In the last two decades, urbanists have restored their thirst for documentation and the dissemination of information by producing precedent-based, practical books again. However, because effective master planning takes years to implement, and because the re-birth of cities has just begun over the past two decades, many recent books in the field are largely comprised of visions for the future. Dhiru’s book is especially refreshing because it includes a great body of recently built work, which takes the manual beyond theory and makes it valuable to urban design practitioners working with even the least adventurous clients.

This book illustrates how the practice of urban design has matured in recent decades. Prior to World War II, there were many resource books of this typology. In the years following the war, symmetrical with a lack of interest in city-building, effective books on urbanism disappeared as well. In the last two decades, urbanists have restored their thirst for documentation and the dissemination of information by producing precedent-based, practical books again. However, because effective master planning takes years to implement, and because the re-birth of cities has just begun over the past two decades, many recent books in the field are largely comprised of visions for the future. Dhiru’s book is especially refreshing because it includes a great body of recently built work, which takes the manual beyond theory and makes it valuable to urban design practitioners working with even the least adventurous clients.

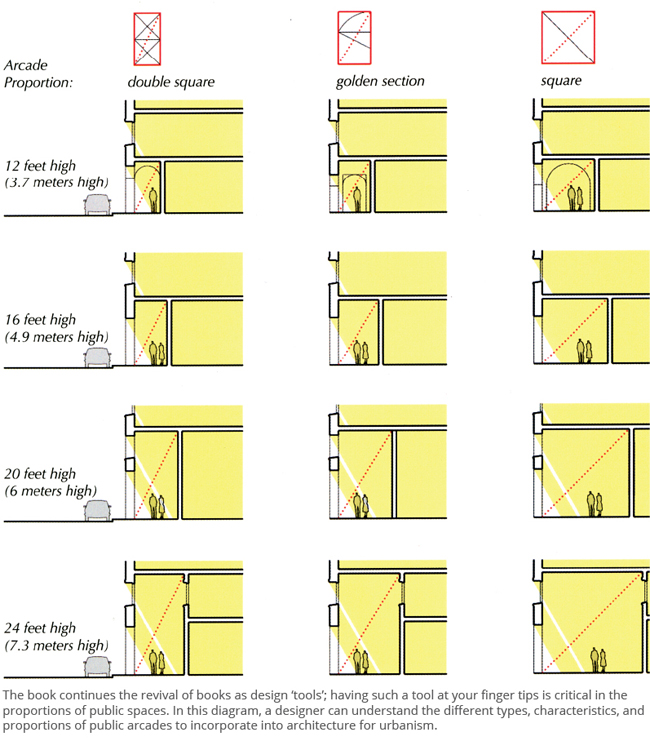

Urban design practitioners endeavor to restore urban environments in the face of incredible obstacles. Design proposals weave competing political, social, aesthetic, financial, and environmental interests into a seamless fabric. The best solutions to design challenges are often bold, and having the appropriate information on hand at the right moment is critical to moving forward. We rely on precedent examples to learn, leverage, educate, and eventually implement these bold solutions. This book will prove to be an outstanding tool at the core of these efforts.

As I page through the book over and over again, I am reminded of a quote in the introduction to Charles Correa’s book Housing and Urbanisation: “As Jaque Robertson has so brilliantly pointed out, you can’t design a spare part without understanding what the machine should look like, and you can’t conceptualise the overall machine if you can’t design a spare part – and that American downtown (being imported indiscriminately all around the world) is just a bunch of spare parts with no one responsible for the whole machine.” It is true: here in the United States, we are living amongst a bunch of spare parts. And here, in this book, we have a wonderful set of tools to help us understand the machine. Dhiru has provided us with a challenge to use this document to its best effect. So, thank you to Dhiru and your colleagues. The rest is up to us.