Alfred Hitchcock was an indirect part of my architectural education at Carnegie Mellon University. The professor who taught one of my strangest studios had a list of recommended media that included Vertigo, along with an album by the Flaming Lips that required four CD players to listen to. I also remember (somewhat more fondly) seeing a few of Hitchcock’s other movies, including Rope and Strangers on a Train, when they were playing in the University Center for $1. But I may never have considered his movies as a kind of architecture until I heard about The Wrong House: The Architecture of Alfred Hitchcock by Steven Jacobs.

Steven Jacobs begins with a simple and compelling idea: to watch Hitchcock’s movies in the service of painstakingly creating the floor plans of the buildings that his characters inhabit. The book imagines Hitchcock an architect, and as such The Wrong House is laid out in the familiar style of an architectural monograph.

The book is divided into three sections. The first two look at Hitchcock’s long career, focusing on the sets designed specifically for his movies and the famous locations that he traveled to to shoot, respectively. I’ll mention here that if you (like me) are going into this book having seen just a handful of Hitchcock classics, it might take some googling to get much out of these first two chapters. The author assumes a basic knowledge of the roles of the personnel on set and often references huge segments of Hitchcock’s filmography. Consider this passage:

“In a way, many Hitchcock films are stories about a house or about the juxtaposition between two houses: The Lodger, Easy Virtue, The Skin Game, Number 17, Jamaica Inn, Rebecca, Suspicion, Shadow of a Doubt, Notorious, The Paradine Case, Rope, Under Capricorn, Dial M for Murder, Rear Window, Psycho, and The Birds are films, the plot and characters of which can be considered MacGuffins for the house themselves.”

After reading multiple sentences like this on every page I found myself wishing that the author had moved the movie references to a footnote, which would have helped these onerous passages be less exhausting to read. If you decide to read this book yourself, you might want to do some homework; even hardcore Hitchcock fans might want to refresh themselves on some of the films most commonly referenced in the early chapters, such as The Birds, North By Northwest, Notorious, Psycho, Rebecca, Suspicion, and Vertigo.

(Great, now I’m doing it, too.)

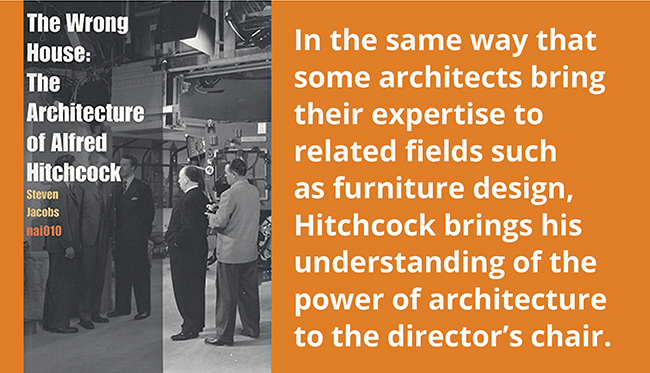

But even casual fans will find that these first chapters contain valuable insights into Hitchcock’s process. For example, as a director he was unusually involved in the design of his sets, possibly owing to his start as a set designer. In the same way that some architects bring their expertise to related fields such as furniture design, Hitchcock brings his understanding of the power of architecture to the director’s chair.

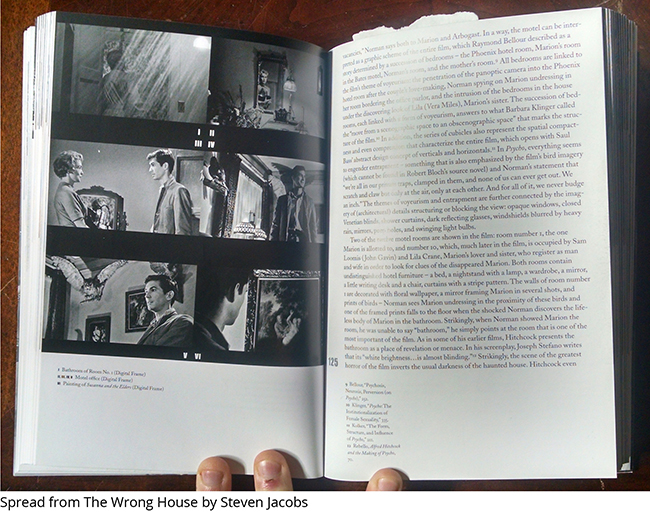

The third section is where the book delivers on its most compelling promise, which is to provide the floor plans of Hitchcock’s famous locations such as the Bates Motel in Psycho. These are not the plans of the sets, but rather the fusion of these sets into the architecture that they are meant to convey. This is no easy task, as I learned while trying to sketch out the hotel at the beginning of The Lady Vanishes (the only Hitchcock offering available to stream on Netflix).

After all, these conceptual buildings are broken down into separate sets specifically because they can’t be filmed as a cohesive building. Walls must be removed to allow complicated maneuvers of the camera, ceilings implied so that overhead lights can do their work, wall angles subtly manipulated to draw the viewers eye around the frame. But Jacobs does an admirable job of re-creating the plans (despite the lack of north arrows, tsk tsk) and rendering them in a style worthy of Architectural Record. I enjoyed reading about the history of the sets and the discussion about their design. I also admire the breadth of the sources that he cites to support his original research, drawn equally from the pools of film and architectural criticism.

On the whole, though, this book is one that does a better job of describing two worlds than it does to bridge the gap between them. There is plenty in the first two chapters to satisfy the cinephile, and plenty in the third to satisfy the architect, but it isn’t as approachable to someone in one of those categories without much knowledge about the other. This schism is also visible in the format; the book was published in 2013, but is designed to emulate monographs published over a half-century ago. I appreciate the nod to the format but the dogmatic adherence to it, down to the dark cluttered photos and the dry academic language, wore thin. I wouldn’t recommend reading this book all at once, but this book has a place on the shelf for the right kind of person. If you’re a big Hitchcock fan or have been meaning to see a few of the classics (still eminently watchable today), the explorations of the imaginary locations in the third chapter make great companion reading to the movies. If only I could still catch them on the big screen for a dollar.