At the beginning of each year, AIA National unveils the newest recipients of the Institute Honor Awards. And each year I scroll through the dozen or so projects, hoping to see one I recognize, hoping to see one of ‘our own’ listed, a local firm receiving this big honor. This year, for the first time in over a decade, Pittsburgh made the list! A huge congratulations goes to Rothschild Doyno Collaborative for their Honor Award for Sant Lespwa Center for Hope. This project has now won an award at all three levels of the AIA – a 2013 Honor Award from AIA Pittsburgh, a 2013 Citation of Merit from AIA Pennsylvania and now this. Columns caught up with Dan Rothschild, AIA and Mike Gwin, AIA after the announcement to discuss the project and what this means to the firm.

Columns: First of all, congratulations on your win; what a huge achievement! I was wondering if you could explain how you came to be the architect for this project, how you were chosen for such an unique opportunity?

Dan Rothschild: Thank you, it’s a great day for Pittsburgh! The client for Sant Lespwa is World Vision, whom we had worked with before, and our history with them is a pretty interesting story. We were hired by them twenty years ago as they were establishing a distribution center near Sewickley, a place for them to collect overstock items from large corporations, which they then distribute to third world countries – a purely functional building. We loved working with them and quickly realized what a great organization they are. Well, they outgrew that first building and contacted us to design their expansion. Our solution was to create the warehouse as an exhibit, to have a place that they could bring potential contributors, in which walking through the space would help tell the World Vision story.

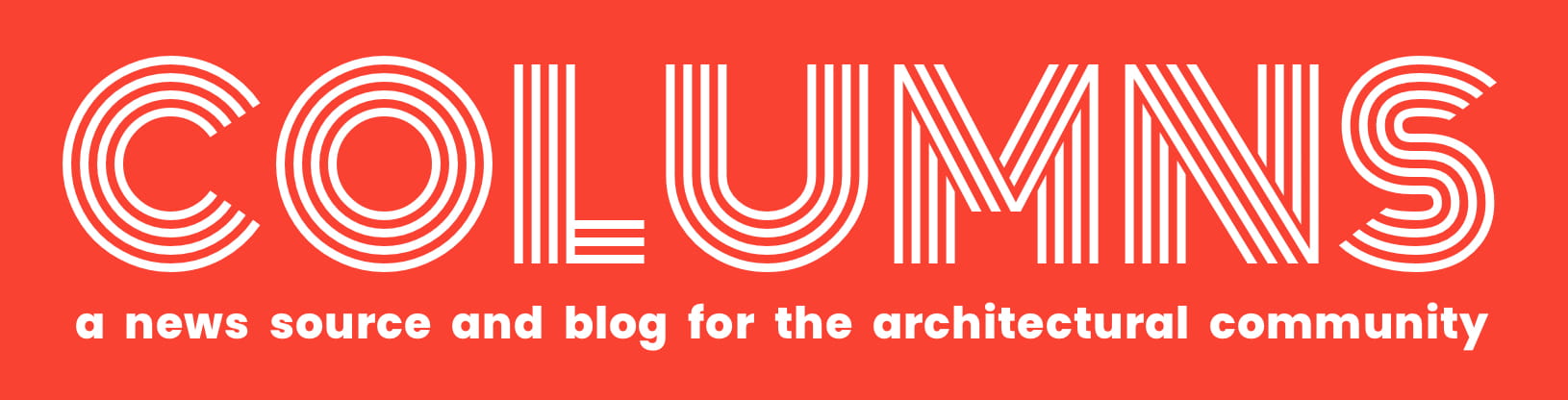

Years later as they were planning a community center near Hinche, Haiti after the earthquake in 2009, someone from World Vision asked us to submit our qualifications. I think WV was intrigued by our design sketchbook, they recognized how that could easily translate the design process to another culture, as community involvement throughout the creation of this center was key. So what began as a small, local project grew into doing this amazing humanitarian project.

Columns: Upon being hired, Mike, you traveled there for a week to meet the community and get a feel for the site. Had you ever experienced anything like this before? Were there any big surprises waiting for you in Haiti?

Mike Gwin: I had, actually. In 2008, I worked with an organization called Shoulder to Shoulder to help design a medical clinic in remote Honduras, and there were a lot of similarities between the projects. We were dealing with similar living and health conditions, the language barrier, sanitation issues. That experience definitely helped prepare me for this trip. We also worked with the youth in the community in Honduras, created an art project to get them involved and feel like they were part of this new building. Likewise, Sant Lespwa was very focused on community involvement. We met with the community elders, leaders, the kids at the elementary school – they were all critical to the participation process.

As far as surprises, even though we had done extensive research on the area, and on the rebuilding and globalization of Haiti, the devastation was still a shock. My visit was almost two years after the earthquake, and throughout the capital, there were still piles of rubble, the capital buildings half destroyed. It was overwhelming to see a country living in that sort of destruction. But their culture is a very positive one, and despite the tragedy that had occurred, they were very optimistic.

Columns: Was it hard to come to a full understanding of the community’s needs, and to then come to a design solution that best addressed those needs?

MG: Well, we knew from our research how large a concern deforestation is for the whole country. Preserving trees was very important.

DR: We wanted to disturb the site as little as possible, to keep the shade trees, to nestle the building into the slope of the landscape, which we discovered was pretty unusual for redevelopment in Haiti. We were really reacting against a lot of what we already saw. We let the environment shape the building.

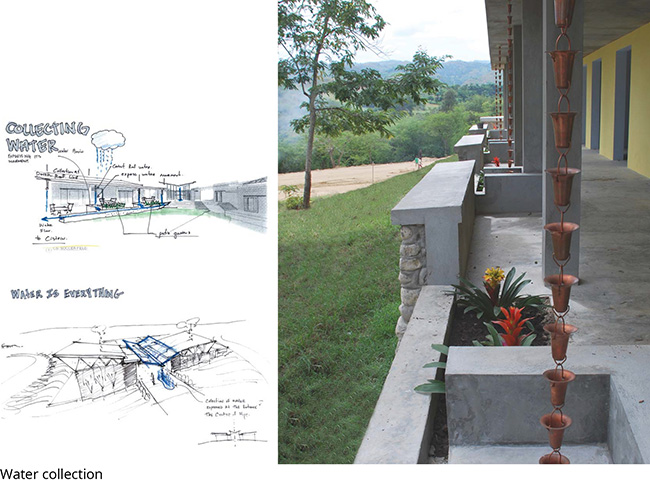

MG: The elders we met shared a lot about the climate-specific needs to make the building comfortable, such as the need for shade. The lack of infrastructure also informed what we could or couldn’t do. Design fundamentals emerged out of necessity. With no pubic water or utilities, you have to think through how to make it self-sustaining. For instance, we positioned the building in such a way that would let the breeze in to cool the center naturally.

DR: There ended up being a real simplicity to the design, even though it’s a net-zero building. Yes, it collects and sanitizes rain water to reuse, etc, but the basic engineering is very rudimentary, employing a septic field, open breezeways and large windows.

MG: Another huge aspect of the project and community involvement was training the locals to be part of the build team, to create job training. They taught us traditional Haitian construction techniques – as cast in place concrete, the use of river rocks in the foundation, thatched shutters woven by the villagers – and we ensured that they were learning valuable trade skills, to be employed during the center’s construction, but hopefully so that they could go and find work afterwards as well. It also really connected the entire community with the project, building a strong sense of ownership and pride in what they were helping to create.

Columns: Had Rothschild Doyno Collaborative ever worked on a project such as this before?

DR: In a third world country, no. But in a community that was dealing with the aftermath of trauma? Sure. We’ve worked in Braddock during and after the closing of its only hospital, as it sought to redefine itself as a community, to build itself back up after a loss. I think the office has a methodology of dealing with trauma within a community via open communication and collaboration, of really involving the people who live and work in such a place. Taking this approach to a global level was a test of our process, and it allowed us to engage with the community, to create success together. I think this Honor Award speaks to the importance of both sensitivity and strength of the engagement with a given community. It’s a small and humble project but it’s made a huge impact on that Haitian village.