This article originally appeared in Columns Magazine in September 2009.

It’s one of humanity’s basic needs. From caves to huts to houses, shelter has changed dramatically as humans sought to better their world. Many housing innovations have had to do with survival, furnaces for warmth, glass windows for protection, while other strides have been in the art of building and the building of art. Nonetheless, humans have been busy perfecting the construction methods of home-building for thousands of years. Each of the new developments in homes had to start with a dreamer architect and a prototype design, be it a Cro-Magnon with a crudely constructed hut or a designer with a neatly grafted blueprint.

And today’s architecture is as rich as yesterday’s with prototype designs and innovations. Modernism, tract housing, and green building have all drastically changed the way we think about our homes. While technology is making it easier for dreams to become reality, many begin to wonder if prototype designs that surpass current construction limitations are useful in a world in crisis.

The City of Pittsburgh has a rich background of innovative homes and buildings. After most of its neighborhoods had been established, local architects focused on filling in the gaps between and within communities. Pittsburgh’s infamous millionaires like Andrew Carnegie and Henry Clay Frick peppered the city with dauntingly striking Gothic buildings like the Allegheny County Courthouse, the Cathedral of Learning, and the unique mansions along Fifth Avenue. All of these buildings helped to make Pittsburgh a forerunner in the ideals of ‘City Beautiful’ design and gained international attention.

Prototype housing in the Golden Triangle didn’t really get it’s start until the early 1900s, when modernist architects like Frederick Scheibler were busy crafting the next generation of housing in their backyards. Scheibler, a Pittsburgh native, was a rebel of architecture in the early 20th century. At a time when other designers were recreating grand Victorian and Gothic-style homes, Scheibler was building sleek, modernist houses. A stunning example of his work is Highland Towers. The U-shaped apartment building, made of yellow tapestry brick and stucco, with inset patterns of blue tile and glass, was fitted with vacuum-cleaning outlets and a prototype air-conditioning system — state of the art technology for its first 1913 residents. Highland Towers is still occupied today, along South Highland Avenue in Shadyside.

The 1930s brought the beautiful homes of Frank Lloyd Wright to the Pittsburgh area, with the internationally renowned Fallingwater and, more recently, the lesser-known Duncan House. Wright designed the the Duncan House to be a prefabricated, mass produced sort of home for contemporary suburbanites. However, only a few of the homes were made and even fewer survive. One remaining prototype was bought, moved from Chicago, and reassembled in Polymath Park in Mount Pleasant Township by local builder and Wright enthusiast, Tom Papinchak. It is one of several Frank Lloyd Wright homes that allows overnight guests and is a major tourist attraction today.

After World War II, Pittsburghers began to realize that the continuation of their overzealous industrialization would leave the city stranded in a changing national, global, and economic environment. They also began to see the damaging effects pollution wrought on their fine city, and strove to stop and reverse the city’s decay. Since the industrial days have passed, Pittsburgh has become one of the best cities for green building and innovative engineering. The city opened its own branch of the Green Building Alliance in 1993 and is consistently among the top three cities under the LEED rating system, with 21 LEED certified buildings in the city (the state of Pennsylvania has 72, second only to California). LEED, which stands for Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design, is considered a benchmark on the road to energy efficient homes. Developed by the U.S. Green Building Council and conducted through the Green Building Certification Institute, LEED ratings take an extensive look at how new or remodeled homes effect the environment. The LEED system is a 100 point system which measures how efficiently a building uses water, energy, and resources. It accounts for sustainability of the building site and resources used, as well as indoor environmental quality and access to transportation. LEED certified buildings strive to serve the ecosystems outside a building and the human inhabitants inside.

One example of a building project seeking LEED certification in Pittsburgh is the Homestead Apartments building on East Eighth Avenue, Homestead. In what was formerly one of the largest industrial neighborhoods in the city, it is a renovated twelve-story apartment building originally constructed in 1959. Overhaul of the old building was extensive; pavement around the building was replaced with native vegetation, which doesn’t require a special irrigation system to survive. Thermostats were set with restricted high temperature levels to prevent waste of energy. The roof was replaced with an energy-efficient roof and all of the apartments were given Energy Star rated appliances. Furthermore, recycled materials were used where possible, construction waste was recycled, and recycling receptacles were provided for residents. The building itself and the construction practices used are excellent examples of how to build or renovate with the environment in mind.

FEELS LIKE HOME

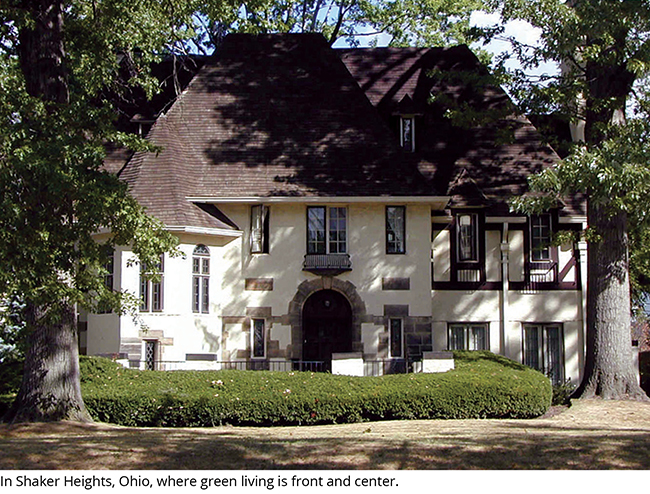

Pittsburgh isn’t the only U.S. city with forward thinking practices. Shaker Heights, a city in Ohio, takes great care to use the best home-building practices when constructing or renovating its homes. The city consists of several close-knit neighborhoods, each lined with trees and close to Ohio’s rapid mass transit system. Shaker Heights officials encourage current homeowners to upgrade their homes with green appliances and materials using federal tax credits and ensure all new homes are compliant with Ohio green building standards. This city is practically a utopia for high quality, green living with its nature center, lakes, farmers markets, and exclusive community services. Even though Shaker Heights homes are not LEED certified, they certainly adhere to the criteria for certification, down to the close proximity of community resources and local markets.

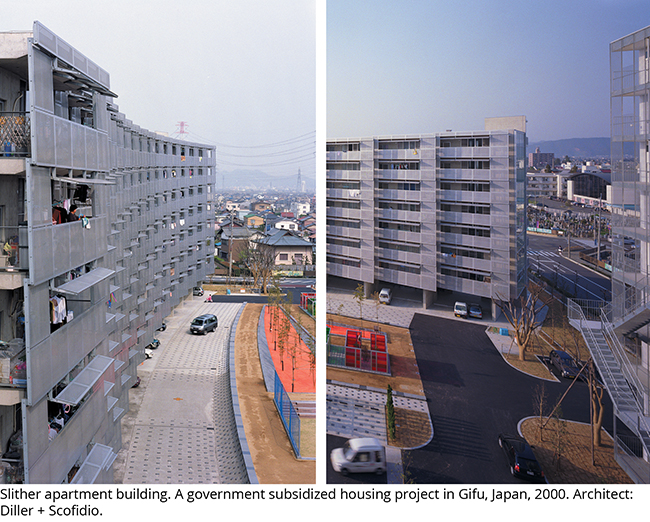

Not all modern prototyping efforts concentrate on green building, although most still incorporate green techniques in their designs. Sometimes, the greater challenge is utilizing urban space while maintaining individuality or incorporating nature into structure. Diller + Scofidio, a husband and wife design team, created the Slither apartment building in Japan, which dispels the belief that mass standardization negates individuality in urban housing. The Slither building consists of fifteen vertical stacks, each seven units high, for 105 units in total. Each unit is rotated 1.5° and vertically offset by 8” from its neighbor, which gives the building a sloping, concave curve adjacent to a communal courtyard. The units all have their own balconies, covered by scale-like, metal screens. Not only does this design create a beautifully reptilian structure, but it also provides privacy and separation for residents, even though they live in identical, adjacent apartments.

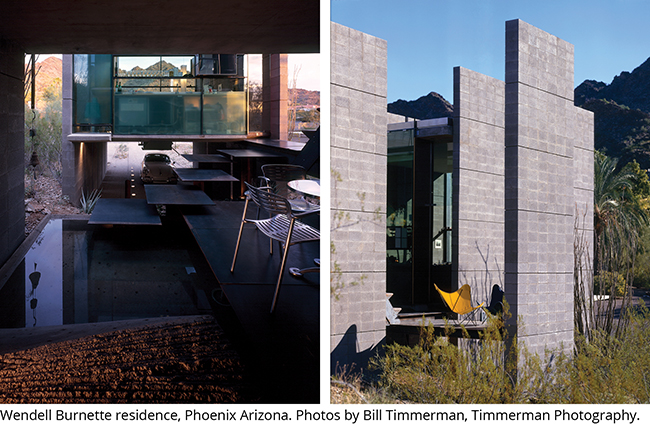

When it comes to making architecture at one with nature, Wendell Burnette, AIA is practically a guru. With strong ties to the Arizona desert, Burnette’s meticulous attention to detail coupled with his love of nature allow him to create homes that are perfectly integrated with their surroundings. His studio and residence in Arizona is a rectangular structure made of foam-injected concrete blocks, open on the sides facing east and west, and closed off from light in the north and south. This takes advantage of the natural (and intense) sunlight of the desert while allowing the house to stay cool and shaded. The walls are also punctuated with small, random-but-not openings, carefully selected to let in light and effectively vent hot air outside. These openings, as well as other open areas of the home, are covered by glass that is flush with the exterior wall or recessed within the wall. Not only does Burnette consider climate when designing and positioning his homes, he considers the view of the landscape from inside the home as well. Because of the openings and windows in the house, one can stand in any place within and see the mountainous landscape that surrounds the home.

INNOVATION AND EXPERIMENTATION

Designs for prototype homes are excellent tools for research and development, and can foster new ideas and innovations for building homes that have less impact on the environment, be it from aesthetics or emissions. But do designs that are too advanced for current means of construction bring less to the table than homes that can be built and occupied today?

Greg Lynn, a modern prototype housing designer, has big plans for the future of homes, even though his houses cannot be produced. Lynn, like many cutting edge architects, uses a digital interface to create his “Embryological Homes”. Their layered, curving, snakelike contours are meant to resemble organic forms found in nature. Each of his designs have similar “DNA”, meaning that although no two homes are exactly alike, they all share similar key traits that connect them, much like various species in the same genus.

Lynn foresees his designs being laser-cut by machines and has already enlisted the help of auto-manufacturing robots to cut pieces for his smaller, more artistic endeavors. His main problem now is finding the right material for homes that can live up to the sleek appearance of the digital designs.

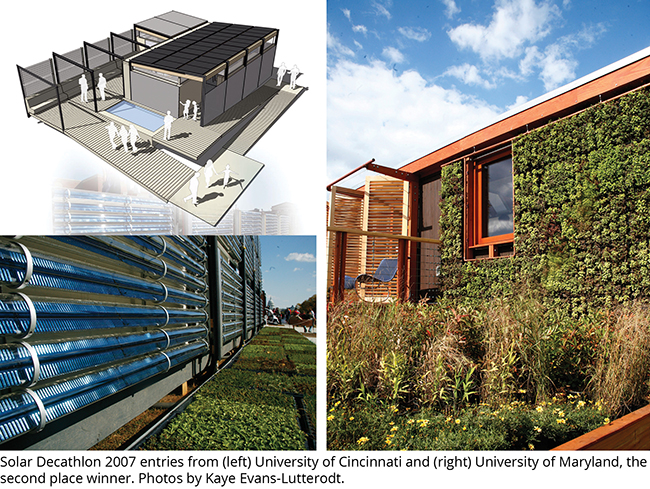

In an interview for Index Magazine, Lynn sums up his feelings about virtual reality, which are akin to his design philosophy: “I always think of [virtual reality] as designing a thing that has yet to be specified or realized. Rather than virtual reality being a space detached from reality, I always see it as a thing that gains something by being real.” Most other architects seem to be designing for today while keeping the future in mind. Great examples of buildable, sometimes reproduced, prototype homes often come from the Solar Decathlon, a competition run by the Department of Energy in which students from twenty colleges across the globe compete to build the best energy-efficient house. Students design and build their 800 square foot homes before the competition, then transport them to Washington, D.C. where the houses are assembled into a “solar village” and judged in ten categories. The decathlon gets its name from these ten criteria: architecture, market viability, engineering, lighting design, communications, comfort zone, hot water, appliances, home entertainment, and net metering. As the name also suggests, each house must use solar energy in some capacity and most strive for a zero-energy home.

With Zero-Energy Homes (ZEH), a house is connected to a utility grid but also relies on solar (or wind) energy for some of its power. The amount of energy used or produced by the home varies by month, but the annual, aggregate calculation of energy use generally balances out to zero, so any energy costs incurred are negated by the energy produced. ZEHs aren’t too different from regular homes; they use most of the same materials, with the exception of a photovoltaic system which processes the energy produced by the home. Photovoltaic cells, or solar cells, use semiconducting materials to absorb sunlight and convert it into electricity by loosening electrons and allowing them to flow freely through the system. These cells can double for roof shingles, building facades, glazing for skylights, and can be fixed or set on a track that follows the sun.

After the Solar Decathlon, most of the solar homes are reconstructed on the building team’s campus or at a nearby museum or research facility. Some have become laboratories for solar energy research, others are used for demonstrations and tours to show the public the future of solar-powered living. Carnegie Mellon University’s 2007 home, for example, has been reconstructed on the Powdermill Nature Reserve in Western Pennsylvania and serves as a great example of a solar home. University of Missouri–Rolla, however, has chosen a different fate for its past entries; all three (soon to be four) homes have been reassembled into a solar village on campus and are rented out to students of the University. And Kansas State University’s 2007 entry was bought by SunEdison, to be used as a demonstrative tool.

The Decathlon’s criteria for success and construction requirements suggest that prototype homes are meant to be buildable, usable, and their effects measurable. This is rather different from the design perspective of architects like Greg Lynn, whose futuristic outlook is shaping the homes of tomorrow. Each method of design has its own merits and brings to light new ideas and innovations for how we live. After reading so much about prototype housing, its design and its function, it is this writer’s opinion that both the conceptual and the functional philosophies are necessary for the progression of housing. While pioneer designers are crafting the future of homes, green builders are helping to ensure that future will exist. To limit prototyping architects to current construction capacities and to discredit futuristic designs for their inconstructable nature is like putting a cap on home innovations. Imaginative and functional ideas together are what make great advancements in architecture possible.

So while the concept of what a house should be has undergone drastic changes over the years, all innovations have had an impact on the future of designing. And with prototype homes the future is now, or at least it is being shaped now.