Experimentation is an essential part of the design process, but is it a secret activity carried out by a team of designers huddled in the studio, or an open process, supported by the client? What makes the magic happen? Ultimately it can happen either way. Ideally it incorporates a little bit of both.

EXPERIMENTATION AND VISION

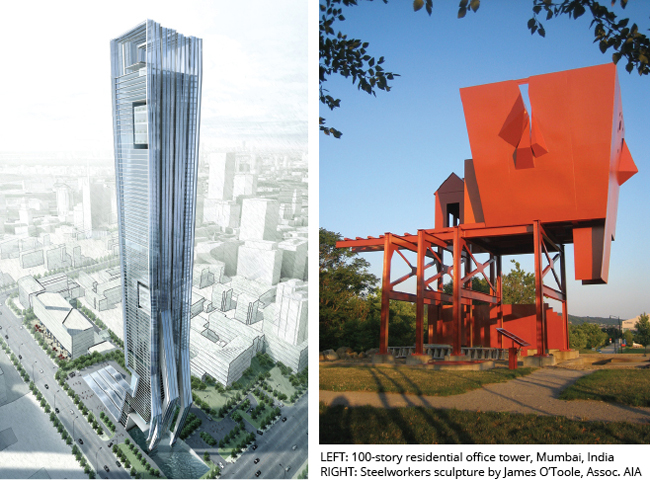

Known for his wildly imaginative designs, Burt Hill’s James O’Toole, Assoc. AIA may be best known for the steelworkers sculpture at the Hot Metal Bridge and the two dinosaurs he designed for Dino Days a few years ago — the “Tonkasaurus” and the winged Da Vinci T-Rex, sponsored by his former employer Astorino. His experimentation and creativity comes from an emotional place deep inside.

Most architects, when asked to come up with concept sketches, study history and context, look through magazines, and examine other similar work to inform the design (as they are taught) and then integrate the elements, through experimentation, to create a design in line with the client’s program. O’Toole doesn’t work that way at all. To him, it’s an emotional-visceral process that perhaps cannot be learned; many of his inspirations come from dreams and observational analogies. His sketches inspire his work, and designs sometimes re-emerge years after original concepts.

“Before I could understand materiality, I had to understand the internal poetic proportions of the space,” he explained. “I don’t think it’s about buildings.”

It certainly isn’t.

O’Toole talked about experiencing a “Chiros Moment.” He described it as that moment when heaven time and earth time intersect; things align and become very clear and you have to seize that opportunity right then, because another one like it may never come along. O’Toole feels that the growth and development in Dubai exposed such a moment, which has, in turn, given him new life and new zeal for his discipline. He has found an artistic home where the experimentation continues within Burt Hill. They have given him the space to live and breathe in his artistic interpretation of architecture.

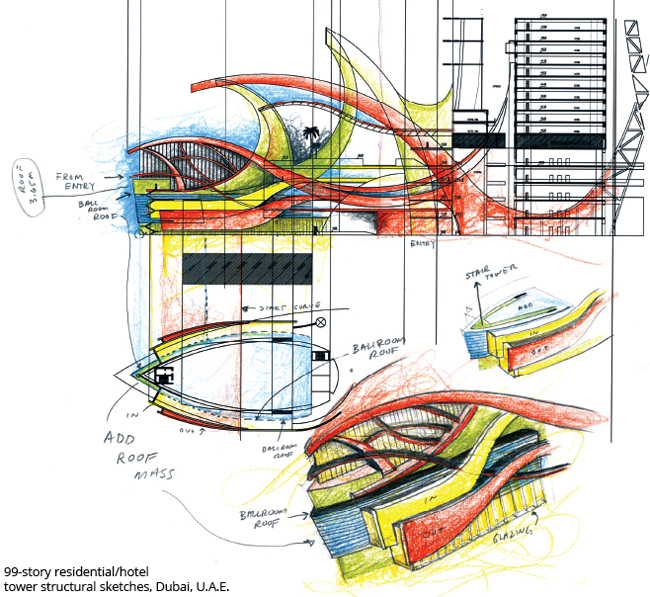

In 2006, O’Toole had the opportunity to create the design for a massive hotel and residential complex in Dubai. The design included a 431-meter tower, 90 stories in steel and concrete, with a 17-story podium that included swimming pools, atria, and restaurants. It was far larger than any project he had designed to date. The podium was comprised of a building pedestal with an intricate array of curved and carved arches and an elaborate tower with a façade of tulip-like leaves wrapping the structure and reaching toward the top.

“At a certain point,” O’Toole said, “I could come up with an exterior design, but when I had to structure it, everyone started running away from me.” Knowing that it was possible to make his “seemingly untouchable” creation into a viable, buildable structure, he met with world-renowned Leslie Robertson Associates, LLC Engineers. He brought them a hand-sculpted physical model that he had built with a laser cutter. The engineering team asked for O’Toole’s Autocad drawing diary of the laser model and the sculpted model, and, after review, simply said to him, “It’s done.” Everything was aligning. The project could finally move forward.

The Dubai building was finally slated for construction until a new client administrative project team came into the company and reevaluated the master plan. The plans for the tower have been put on hold from the development, and construction was halted. Fortunately, another client has shown interest, and the design is now being reconsidered.

For another project, when sharing a conceptual model with the design team, O’Toole explained that they reacted as though the design was complete; they saw it as a “pristine white sketch model.” To emphasize that it was simply a work in progress, he poured his morning coffee over it — shocking everyone but breaking the stifling intensity of the session. From there, the team could freely discuss how the design could continue to evolve. O’Toole has the ability to see beyond what’s immediately in front of him; to see that the root of architecture is more about being sculptural. His buildings allow him to leave the world of the tangible and enter a spiritual realm where he is creating, drawing, sculpting. He goes to the root of the profession, acting not only as the designer, but also the creator and the builder.

CLIENT SUPPORT IN EXPERIMENTATION

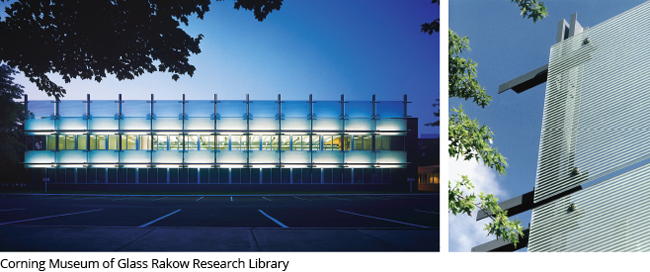

Bohlin Cywinski Jackson is fortunate to have a progressive clientele, which affords them the opportunity for experimentation and research toward design ideas. As an example, previous experimentation with glass at the Corning Museum of Glass — Rakow Research Library has led from that project to other ambitious uses of glass within the firm’s work including several signature buildings for Apple.

Michael Maiese, AIA, was the project manager for The Corning Museum of Glass Rakow Research Library in Corning, NY. The project provided an opportunity to explore the utilization of glass and glazing. The library houses a massive archive with a vast array of published materials on the subject of glass. Corning Incorporated has, over the years, brought in national architects for projects in the area to create a dynamic community – they have been good stewards for the development of Corning, NY. Often the design solutions contained an ambitious utilization of glass technology.

To the BCJ design team the Library project posed another interesting opportunity. Exposure to natural light was a critical design factor because while the books and historical papers can be damaged by natural light, the patrons, researchers, and archivists desired daylight and views. The goal was to accommodate both, and the experimentation began. The BCJ team studied various design solutions in sketch form, computer and physical models, mock-ups and samples, including a few full-scale mock-ups constructed on-site.

Glass technology was not new to the firm, but they had the opportunity to experiment more, with various uses for glass throughout the project. Among the ambitions was an opportunity to create a specialized shading panel, by coating both sides of glass, which would allow views out, but provide shading from the sun. The first challenge was predicting light refraction through the screen panel at different angles through the various layers. A Corning Inc. scientist – who also was an astronomer – volunteered to assist in the development of mathematical formulas while the BCJ team derived empirical information via the mock-ups. The second challenge was fabrication of such glazing. A key fabrication challenge is that glass cannot be coated on both sides, and exact tolerances are virtually impossible to achieve. Thus the final collaborations were with the glazing fabricator to marry the technology with the design ambitions to produce the custom glass shading panels. “If it weren’t for the client, this extended experimentation may not have happened,” Maiese said. “They had an appreciation for the design value and the patience for it.”

Since that experience, using expertise gleaned from the Rakow Research Library experiments and continuing relationships developed with designers, engineers, and fabricators during the process, Maiese and the firm have had the opportunity to incorporate various developing glass technologies into other of the firm’s designs. “A great deal of energy goes into coordinating all of the technology into a design to make it look very simple,” he added. “The amount of effort to make it all work is stunning.” As is the result.

A CAUTIONARY TALE

Andrew Moss, AIA is the principal of a 6-person firm in East Liberty, open since 2006. His own firm emerged after 15 years with Semple Brown in Denver, CO. In his experience, experimentation can sometimes come with less-than-stellar results.

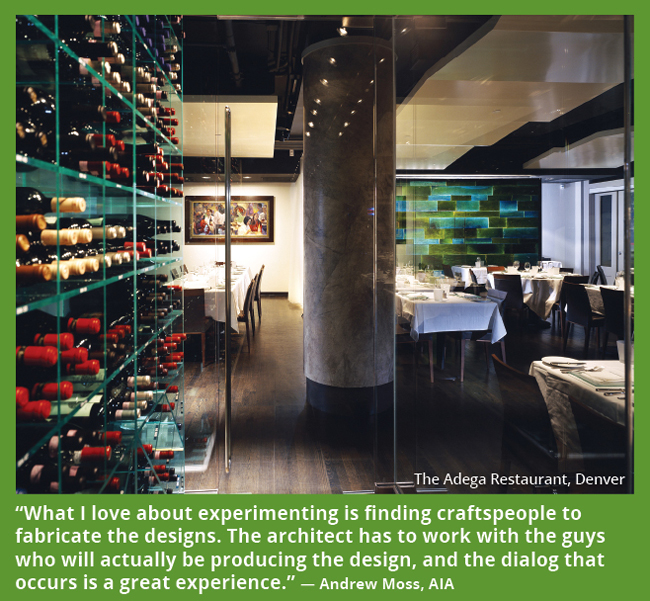

Before coming to Pittsburgh, he designed the Adega restaurant in Denver. “The clients were very open and wanted a contemporary design,” he explained. His two experimental features evoked the west’s expansive sky and the stone piles that were a remnant from the region’s mining history.

The first was a series of ceiling planes that were folded and spanned the ceiling. That element was a great success and worked well for acoustics and lighting. The other feature consisted of two stone walls, one made of real stone, clean and stacked, intentionally detailed in a stainless steel frame. The other was a glowing resin stone wall. He found a fiberglass craftsman and worked with him in his shop. He met with his clients and showed them colors and samples, and believed that everyone on the client team was on board. In his mockups, light glowed through the wall in a bold visual terminus. But, the built result wasn’t what was expected and the client was displeased. Moss ended up having to tear it out and rebuild. “It was a real mess,” he admitted.

Having gone through that, he explained that “it cost a lot of money and while not perfect in the end, I was satisfied with it.” He believes if the team had been clearer about the fact that the fiberglass wall was an experiment, everyone’s expectation would have been more realistic.

That experience has not dissuaded him from trying new things again. “It was so exciting,” he said. Since then he has incorporated fiberglass into other designs that have been very successful. “What I love about experimenting is finding craftspeople to fabricate the designs. The architect has to work with the guys who will actually be producing the design, and the dialog that occurs is a great experience.”

Moss said he learned a lesson: Make sure you talk to your client so that they understand the inherent risks in doing things unconventionally.

BASED IN MATERIALS

“I’ve never drawn a line between art and architecture,” said Sylvester Damianos, FAIA about his more than four decades of practice. He is well known in the Pittsburgh community as both an artist and an architect. His art, especially his wood reliefs, embody his ability to draw out the innate design structure of the material. Perhaps it isn’t experimentation per se, but his sculptural sensitivity has enhanced the work of others.

In 1984, Fritz Sipple, FAIA, from DRS (Deeter, Ritchey, Sipple) asked him to consult on the (then called) Westinghouse Energy Center in Monroeville. The issue was a free-standing 85-foot long granite wall designed to screen the entrance to the company dining facilities. DRS conceived the wall as an art gallery and wanted to talk about the details of hanging and special lighting. The suggestion to turn the wall into a piece of art was accepted by both Westinghouse and DRS and the collaboration resulted in a sculptural grid of gently curved aluminum shapes, created by Damianos.

Over the years, Damianos has been commissioned by more than ten other architectural firms to incorporate art in their work — a fact that he is proud of.

A STUDENT AND TEACHER

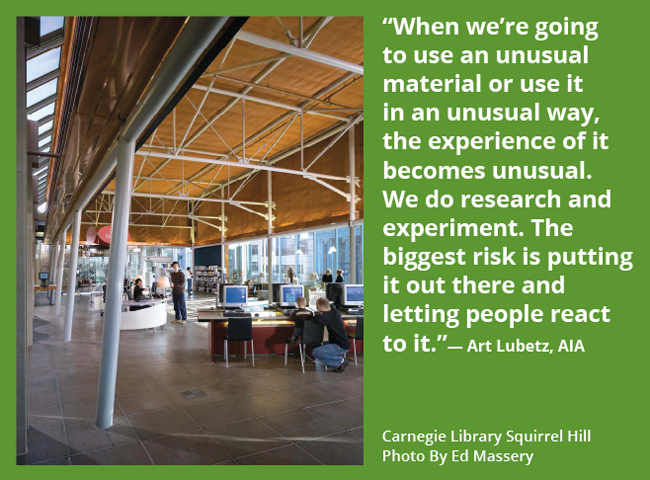

Originally an art student, Art Lubetz, AIA now focuses on design solutions that rise from experimentation. At Lubetz Architects, he explains, “Our work is very inexpensive. We’ve never had a big budget for our work.” Lubetz used to think that was a limitation, but now it’s one thing he enjoys working around in finding creative solutions with relatively low-cost materials. He said that the larger challenge is to find contractors who will work with the firm and not raise their price because they are asked to create elements they haven’t built before.

For the Carnegie Library Squirrel Hill, Lubetz ran a series of tests with different materials. They created one feature shaping copper insect screen with black acoustic insulation behind – simple and visually interesting. He explained that they worked with contracting firm Easley and Rivers and they were cooperative and helpful. “The actual workmen make it a pleasure many times.”

He added that they get their work built by being pretty maniacal about what it costs and adhering to budgets, which means experimenting during the process. “When we’re going to use an unusual material or use it in an unusual way, the experience of it becomes unusual. We do research and experiment. The biggest risk is putting it out there and letting people react to it.”

Lubetz adheres to the firm’s philosophy of creating experiential architecture, but doesn’t reach overboard to create sculptural elements. He offered that his projects may appear more sculptured due to the places they’re in and the users’ experience of being in and moving through them. He added, “We engage the embodied mind in the space.”

In addition to experimenting with his project team, Lubetz explained that his students at CMU have been the key to many project successes. “I cannot impress enough how much I’ve learned from my students in the last 20 years. I teach what I do so what I do becomes more informed because 12 to 14 students have dialog in the classes. I can’t tell you how rewarding that is.”

IT ALL COMES BACK TO DESIGN

After 13 years at EDGE studio, Dutch MacDonald, AIA has shifted into a field with parallels to architecture, but takes it into a new realm. He is proud of the work developed during his years at EDGE, and found the work extremely fulfilling, but this was a change that has moved his career forward.

Since March, he’s been the Chief Operating Officer at MAYA Design and is enjoying parlaying his design expertise to work with their broader scope — a scope that relates to graphic design, industrial design, the influences of computer design/technology, and of course, architecture. “I was intrigued with MAYA and their philosophy of Pervasive Computing — the idea that information is not only in devices, it is all around us,” he explained. “This creates a paradigm shift of what space is and how we understand the relationship between architecture, space, and planning.”

MAYA does a lot of internal research and development, and they are currently experimenting with systems on their own. One experiment is on how to run ideation sessions (translate: meetings). MAYA’s main conference room is the Kiva, a round room that has white boards on every surface, whose name references the round underground chambers used by the Pueblo Indians. A brainstorming session can work its way around the room and at the end of the day people can see all the ideas and put them together. The team first started to enhance the room with digital tools and are now working with a prototype technology of their own design. They can record an entire meeting on a 360-degree camera — Kivo technology in the Kiva. One piece of technology uses a Nintendo Wii. There is a secondary camera that captures where they are in space and records them talking. Each person in the meeting is connected. If something is relevant to them, they can hit their name tag and bookmark the moment and the system records the last 30 seconds of discussion for them. Then, at the end of the day, the camera captures the entire circumference of white boards.

Using this technology in a productive way is the goal. “Results are fine if they’re meaningful,” explained MacDonald. “If you aren’t doing usability studies with real users, you may not be uncovering their true unmet needs.” They want to get their prototypes in front of end users as quickly as possible to make something better.

In the end, they want their process — whether it’s a building system, a gadget, or the ambiance of a public space — to be meaningful to people and still be easy to use. The challenge, through their experimentation, is to hide that power and let people simply do what they need to do.

These stories illustrate the kaleidoscopic emergence of design through experimentation and artistry. Experimentation, whether via trial and error, research supported by the client, dreamscapes, or just creative play with materials from our local hardware stores create projects with a unique expression.