Valeriano Zarro, AIA tells us Place-Specific Design: Architecture for Visible Sustainability is a ‘guidebook’ for architects and architectural students who are interested in sustaining the cultural and ecological specificity of place. Extensively illustrated examples comprise more than half of this relatively short and manageable book, with a preface by Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa. Zarro – a former Pittsburgh architect who ran a popular cafe on the South Side in the 1990s – offers several fresh insights on an increasingly common theme within our profession, namely making architecture that integrates ideas about 1] localized place-specific character, 2] multi-dimensional user wellbeing ,and 3] sustainability in terms of both nature and culture.

The book includes 3 distinct parts: the aforementioned architectural examples, Zarro’s theoretical text with extensive quotes by other thinkers from diverse fields of the human and environmental sciences, and a thoughtful critique of current architectural practice in a preface by Juhani Pallasmaa.

Juhani Pallasmaa’s preface entitled ‘Biophilic Ethics and Aesthetics in Architecture: Human Nature, Culture and Beauty‘ offers a critique of current globalized architectural practice.

“Today’s globalized, instrumentalized, technologized and commodified construction eradicates forcefully the sense of specific place and identity. Instead of serving purposes of cultural rooting and human empowering, the constructions of our consumer culture tend to benefit the investors and to accelerate estrangement and social discrimination, the “existential alienation” that Edward Relph identified…”

“Today’s globalized, instrumentalized, technologized and commodified construction eradicates forcefully the sense of specific place and identity. Instead of serving purposes of cultural rooting and human empowering, the constructions of our consumer culture tend to benefit the investors and to accelerate estrangement and social discrimination, the “existential alienation” that Edward Relph identified…”

“The fashionable architecture of our consumer world today seeks to seduce the eye, but it rarely contributes to the integrity and meaning of its setting. It aspires to support the business of construction, not architecture as a lived metaphor of dignified life. Instead of supporting the large collective, buildings become a medium of social inequality.”

Pallasmaa’s critique focuses on two issues: 1] our [perhaps unwitting] service to a commercial-industrial complex that often creates shallow and dehumanizing but profitable real estate, and 2] technological advances that allow us us to dress up that profitable real estate in designs that express an ego-driven desire for novel solutions rather than create great places for people.

His recommendations for a better path are reflected in his title, particularly the key words ‘biophilic ethics’ and ‘beauty’.

“The call for an ecological ethics, lifestyle, and sustainable architectural thinking, is surely the most important force of change in architecture since the breakthrough of modernity and functionalist rationality a century ago.”

“It is most likely that in the near future the models and metaphors of thought and design, from everyday technology to computers and material sciences, and from economics and medicine to architecture, will increasingly be based on biological imagery, not bio-morphic forms, but the incredible subtlety and dynamic complexity of biological systems in their interaction, dynamic balance, and emergence. The world is evidently much more complex and refined than we have been taught to think, and this applies to ourselves as biological beings.”

Pallasmaa argues that we need to stop thinking of people as being separate from nature, but rather see humanity’s technology and culture as extensions of nature. His biophilic ethics is not a simplistic appeal to use more indoor plants, but a deeper commitment to design a built world that both performs and is experienced in ways similar to the natural world. Natural environments are almost always more beautiful than built ones, also more resilient, more adaptable, more diverse, more healing and more restorative. He argues that forsustainable design to be truly sustainable it must be beautiful in the same ways that nature is beautiful.

Lance Hosey, in his book The Shape of Green, makes a similar argument, as does Michael Mehaffy and Nikos Salingaros in their book Design for a Living Planet. As we focus on our evolutionary past perhaps a new humanism might emerge, one based in our biology.

“We all have a tail bone as a reminder of our arboreal life, the remains of a horizontally moving eye-lid, the plica semilunaris, in the corner of our eyes from our Saurian phase as lizards, and we have traces of gills from our primordial fish life in our lungs. We must have similar mental remnants in our genetic and collective memory. In fact, Sigmund Freud made the assumption of the existence of “archaic remnants” as he theorized the unconscious human mind. This is one of the truly revolutionary intellectual breakthroughs of the modern man, but still largely ignored.”

Pallasmaa leaves us with questions: How might this become a model for an architecture that is both more humane and more ecological? How can we make places that are truly adaptable and beautiful, rather than merely stylish or edgy? “Even our aesthetic desire and longing for beauty have to be seen in an existential and biological perspective, not as a mere source of momentary pleasure, or as a marketing strategy.”

Zarro provides some possible answers as he builds on Pallasmaa’s themes of integration and deepens them in his text. Some of these themes set up pairings like human/nature, technology/biology, local/global, ecological/cultural, technical/experiential, purpose/aesthetics, organism/environment, efficiency/diversity, rational/emotional, project/context, place/real-estate, and novel/good. His ‘guidebook’ doesn’t provide a checklist or a set of rules, but rather they offer a mindset shift.

A good place to start is with the organism/environment pair:

“I have proposed that we consider ‘organism-environment’ as a single integral evolutionary unit in order to overcome what Bateson refers to as the inevitable ‘split’ between man and nature due, in part, to restrictive notions of self as well as to the arrogance emanating from increasing technological power. “

Building on the unity of person and place Zarro argues that the key to meaningful placemaking is framed by the local/global pairing:

“The emphasis that visibly sustainable architecture must emerge, in part, from site-specific characteristics ensures potential ‘consubstantiality’ between an imposed Idea, and the manifestation of that Idea as Form that is relevant to the unique culture and ecology of place. The emphasis on integration between universal ideals and local characteristics gives Place-Specific Design a character that is both ‘abstract’ and ‘narrative.’ It is modernist architecture ‘rooted’ in place.”

If we define the basic unit of life as organism-environment rather than organism alone then our sense of self is inseparable from our sense of place. As Alain de Botton has written: “We are, for better or worse, different people in different places” [The Architecture of Happiness]. The global can subvert our sense of place in a couple of ways: first by offering a one-size-fits-all sameness our sense of self is disrupted; and second by prioritizing newness and the rapid cycling of style/fashion we lose a sense of stability that authentic place often provides. Nassim Nicolas Taleb has written that “Change for the sake of change, as we see in architecture, food, and lifestyle, is frequently the opposite of progress” [Skin in the Game].

Zarro’s other central argument is for a broader definition of sustainability. Beyond resource conservation [energy/water/materials] we have to think about biodiversity and how it is affected by real estate development. And if we think of humanity as an extension of nature rather than something separate from nature, then cultural sustainability -particularly local and diverse culture- needs to be included as well. Issues like biodiversity and human equity, justice, and inclusion weave together. Environmental health and human wellbeing arise as two parts of the same issue.

Zarro’s other central argument is for a broader definition of sustainability. Beyond resource conservation [energy/water/materials] we have to think about biodiversity and how it is affected by real estate development. And if we think of humanity as an extension of nature rather than something separate from nature, then cultural sustainability -particularly local and diverse culture- needs to be included as well. Issues like biodiversity and human equity, justice, and inclusion weave together. Environmental health and human wellbeing arise as two parts of the same issue.

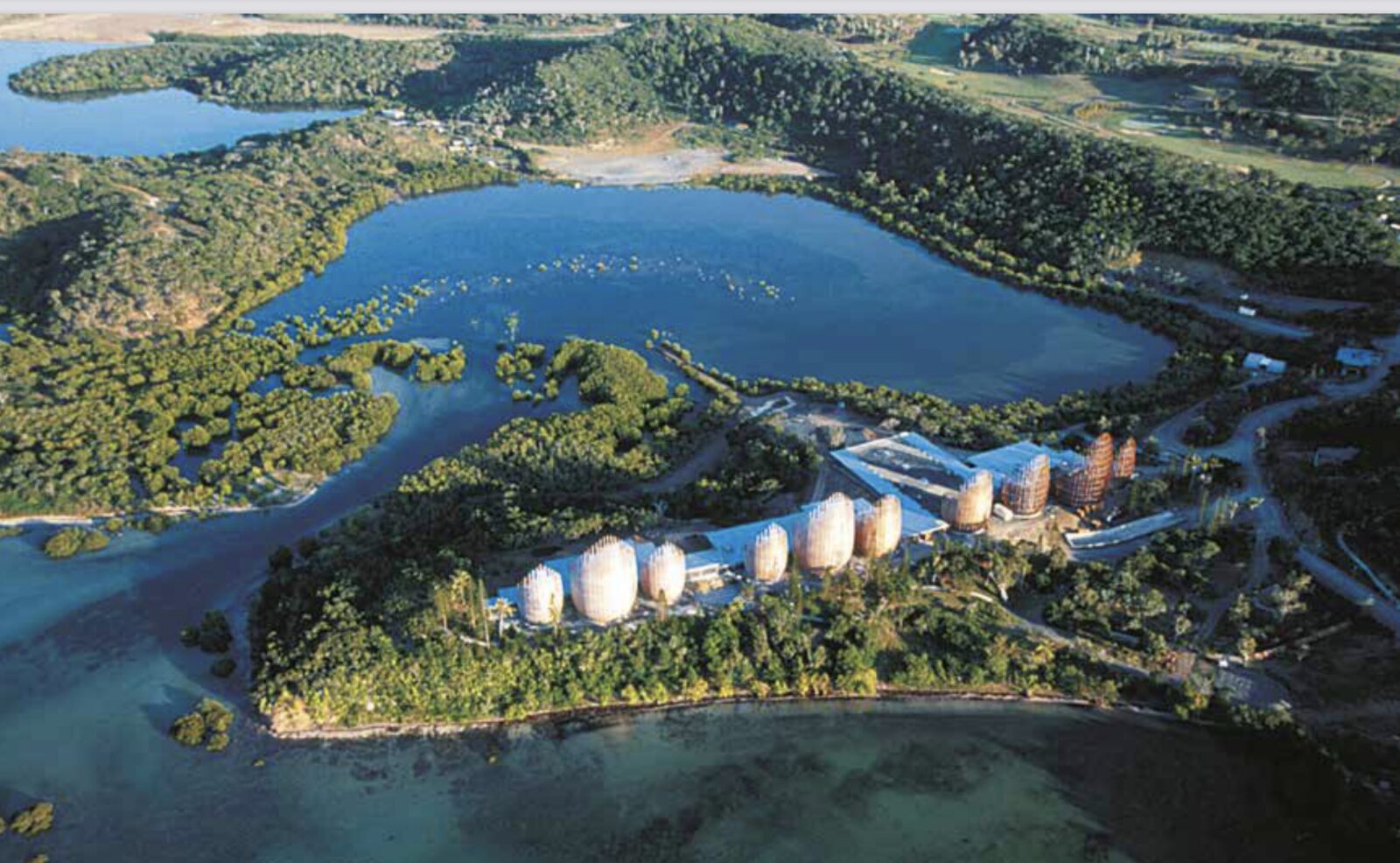

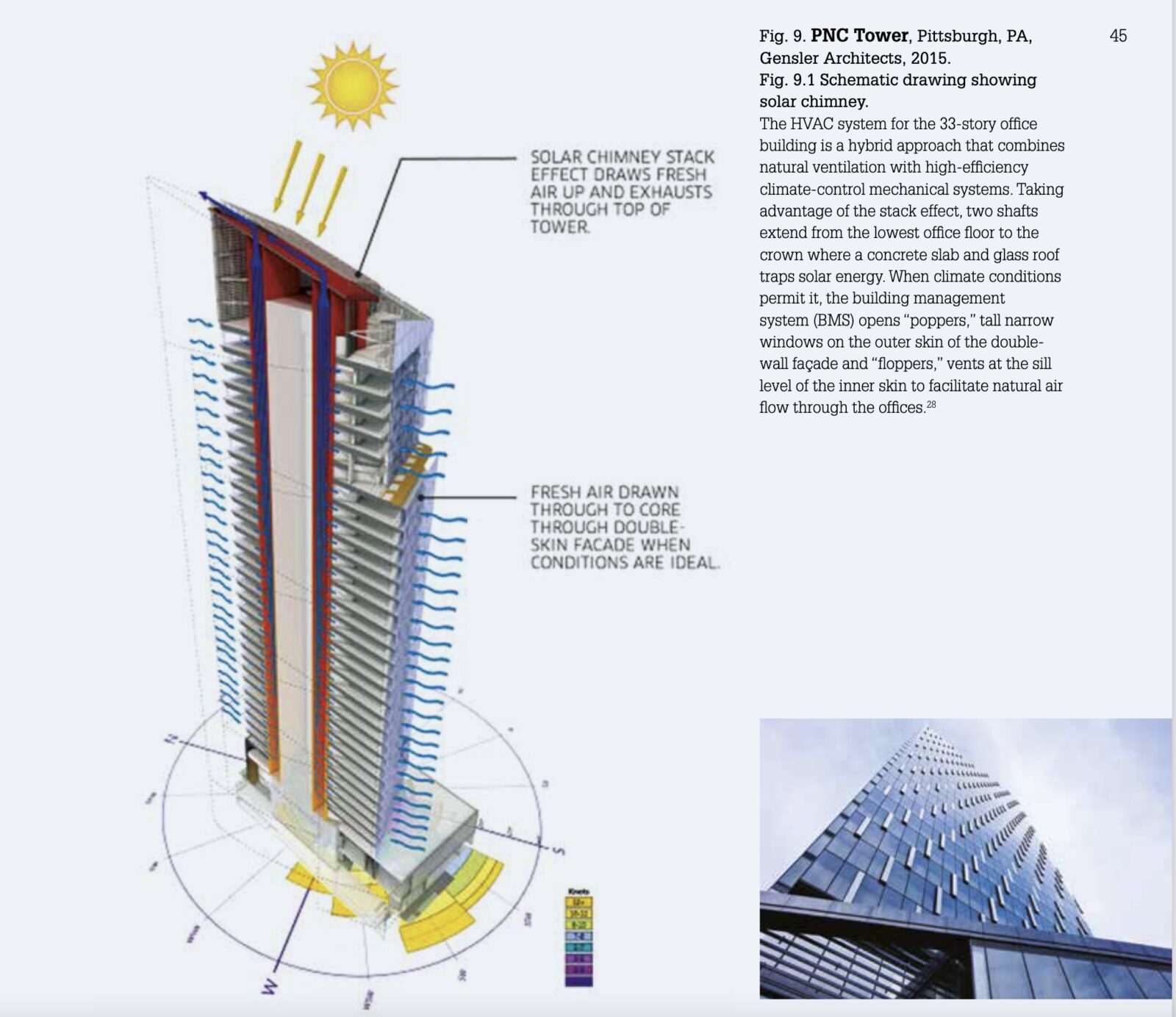

The third and largest component of the book is comprised of a widely diverse set of project examples. Everything from advanced high rises like the PNC tower here in Pittsburgh to indigenous architecture made of local materials, and many in between is included. Most of the examples are not widely published so the reader is likely to see several new things. Each example has a fairly extensive narrative that attempts to connect the example to the ideas presented in the text. Unfortunately the narrative often depends heavily on marketing blurb written by the architect of the project, and as is often the case, the design doesn’t always seem to do what the words promise. Still, overall the examples are interesting and challenge the status quo.

Architectural practice as a business enterprise cannot operate outside of the ‘commercial industrial complex’; and as cultural artifact architecture cannot live outside the media driven fashion/style rapid cycling insanity, but we have to find ways to rise above. Our job is to make the world better through architectural design, and that means we have to prioritize good over novel, and local over global. We are often charged by our clients to follow global real-estate formulas [like 5 over 1 stick built housing] and try to dress them in stylish novelty; unfortunately the real-estate formula and the stylish novelty rarely result in sustainable, adaptable, beautiful places that help people and planet flourish. Zarro’s is one of several voices today seeking integration between design for wellbeing and sustainable design, between beauty and performance, between ancient wisdom and contemporary innovation: and one worth hearing.

Place-Specific Design: Architecture for Visible Sustainability is available for purchase online.

F. Jeffrey Murray, FAIA of Cannon Design is a past President of AIA Pittsburgh, an avid golfer and a voracious reader.

F. Jeffrey Murray, FAIA of Cannon Design is a past President of AIA Pittsburgh, an avid golfer and a voracious reader.

Dear Mr. Murray,

What is pleasant surprise to read your excellent and totally unexpected review of Place-Specific Design. I greatly appreciate the way you tied the themes of the book to other writers who have similar interest. Thank you very much. Best wishes, Val