It starts with a meeting, a seed of concern that grows into a dialog, rooted in the heart of a city. Size, demographics, and location differ at every meeting, but the topic is always the same: how can we make our community safer, more diverse, more livable, and more prosperous? The discussion morphs into analysis. Residents, public officials, police, and community leaders all lend a voice or a concern to address the issues. Market and city data is scoured and absorbed. A plan of action is made and a community development corporation is born.

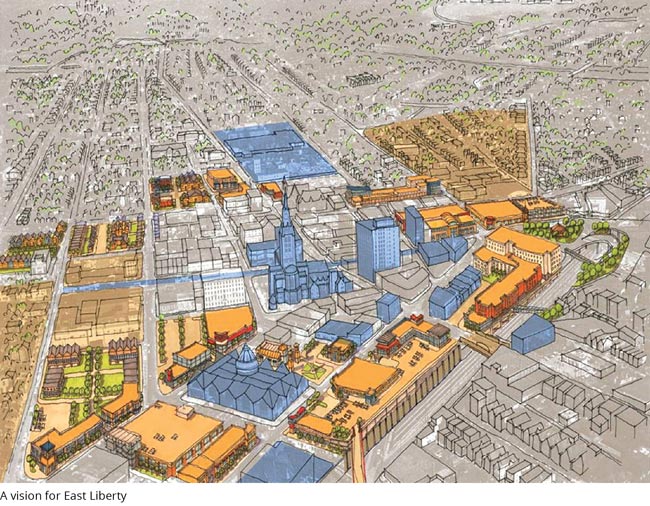

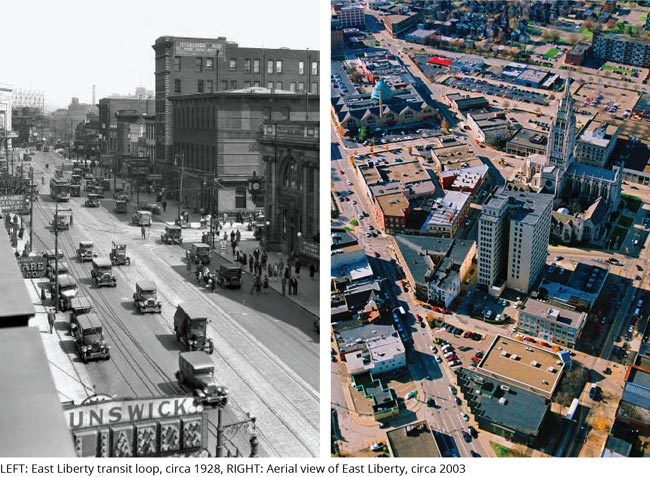

Reinventing East Liberty

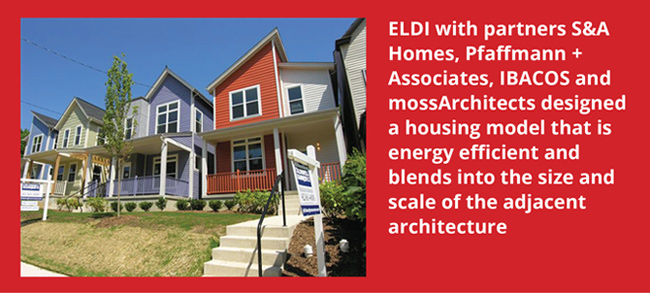

Pittsburgh is no stranger to Community Development Corporations (CDCs), as the city has been subject to many serious revitalization efforts since its decline after the fall of Big Steel. One local CDC with big plans is East Liberty Development Incorporated (ELDI). They have been working in the community since 1979 to bring businesses and denizens back to East Liberty. One of their priorities is to provide affordable and energy efficient housing for all residents. They have established housing for homeless mothers recovering from substance abuse through the Sojourner MOMS project. These projects help parents get back on their feet and reunited with their children, repairing their relationships and strengthening the community.

A major housing project ELDI helped facilitate is New Pennley Place, a mixed-income residential community named for its occupancy of the corner of Negley and Penn. New Pennley Place is an attempt to fix the errors of the Urban Renewal Project of the 1960s, which had previously built a HUD-insured apartment complex on the site. By 1997, that complex had significantly deteriorated and many homes were left vacant due to defunct mortgages and poorly maintained properties. This is when ELDI partnered with The Community Builder’s Inc. (TCB) to reclaim the property and replace the dilapidated homes with new, mixed-income housing with safe, public spaces. TCB, a national non-profit organization specializing in housing revitalization, initiated the several stage renovation and transformed nearly 200 homes. Those still residing in the old HUD housing units (and were in good standing) were allowed to stay during the construction and move into one of the new homes, often with the unexpected surprise of lowered rent, courtesy of TCB’s mortgage refinancing, and lowered utility costs.

ELDI is no stranger to inventive solutions to its housing, either. In 2007, they purchased an abandoned building on Rippey Street after East Liberty residents thwarted plans to convert it into housing for ex-cons. ELDI’s innovative resolution for this property was to transform it into a co-housing unit. With co-housing, residents have their own apartments or houses but share public spaces like fitness rooms, dining halls, and rec centers. Like the rest of ELDI’s new housing, the building would be fitted with a green roof and solar panels to make it more energy efficient and affordable for its residents. While the project was determined to not be feasible at this specific locale, ELDI learned a lot from the process; to create co-housing is to find a near-perfect match – the right piece of real estate, a common vision among all partners, and finances to support that vision. ELDI continues to encourage residents to work together and strengthen the community.

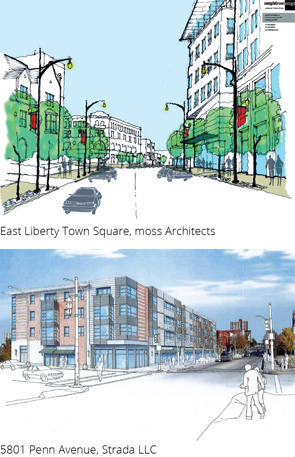

Another goal for ELDI is attracting business to East Liberty. They have already made a difference by creating a Small Business Loan Fund and Advisory Committee, allowing small businesses like the Shadow Lounge and Abay to thrive in East Liberty alongside larger corporations (also enticed by ELDI) like Whole Foods Market and Borders. To further the commercial revitalization efforts, ELDI is partnering with the City of Pittsburgh to make  Penn Circle more navigable by removing concrete islands, reconnecting streets in a grid pattern, restructuring curbs and sidewalks. The biggest change, however, transforms the one-way section between South Highland and Collins Avenues into a two-way street. The intent is to allow traffic to flow more freely to and from East Liberty and give the business district back its “main street” feeling.

Penn Circle more navigable by removing concrete islands, reconnecting streets in a grid pattern, restructuring curbs and sidewalks. The biggest change, however, transforms the one-way section between South Highland and Collins Avenues into a two-way street. The intent is to allow traffic to flow more freely to and from East Liberty and give the business district back its “main street” feeling.

Paving The Way

Funding the Penn Circle renovations is the Urban Redevelopment Authority of Pittsburgh (URA), which has been shaping the city since 1946 when it was one of the first restorative agents in Pennsylvania. They take some of the first steps in rehabilitating vacant houses or contaminated building sites, and pave the way for CDCs to build new houses and shops. They also work with communities to assess their needs and develop a plan of action, even educate local leaders about their options and how to take full advantage of their opportunities. The URA also has programs aimed at helping home buyers and home owners. The Pittsburgh Home Ownership Program offers below market mortgages to home buyers. Another, the Pittsburgh Home Rehabilitation Program, offers 0% loans for up to $25,000 to help home owners make necessary renovations.

Some of its more unique undertakings, however, are the many brownfield sites that the URA has reclaimed and rehabilitated in the years since the end of Pittsburgh’s industrial days. Brownfield sites are contaminated parcels of land that, typically, were once industrial factories and mills which have long since been abandoned. These toxic areas are often devoid of life and can be very difficult and expensive to restore. Given Pittsburgh’s notorious industrial history, it’s not difficult to believe that there were many brownfield sites all over the city.

One of the URA’s first brownfield projects was Gateway Center, near Point Park, which is still in use today. More recent brownfield projects include the South Side Works. This 123 acre property, once the home of the LTV Steel Finishing Mill, deteriorated into a toxic brownfield river site when the steel industry plummeted. The URA acquired the riverside property in 1993 and since then, has given out over $14.6 million in grants and loans to fund businesses, which, along with investments from the private sector, has rehabilitated the land and attracted national companies like American Eagle Outfitters to invest in Pittsburgh’s South Side. According to the URA, property values for nearby buildings have shot up between 160 and 220% over the last 8 years. When compared to the city average of only 20% during the same time period, the impact of the South Side Works rehabilitation on the area is made abundantly clear.

Encouraging Collaboration

Another CDC shaping the region is Pittsburgh Partnership for Neighborhood Development (PPND). Formed in 1983, the PPND is an intermediary that connects communities to resources, investors, education options, and others with common goals. They encourage different neighboring communities to work together to achieve similar goals and collectively apply for funding. They also provide funding for training local leaders in fields like business, real estate, and finance, and help those leaders strategize to find the best solutions that fit their neighborhood’s specific problems.

In 2007, the PPND partnered with private organizations and government officials in Pittsburgh to form the CD Collaborative. Their mission was to pool their resources to accelerate revitalization across the city and increase their level of impact. They studied city data and best practices from other coalitions in the nation, and decided to focus on four main regions in the city: the Allegheny City Corridor, the East End Corridor, the Greater Uptown Corridor and the Southern Hilltop Corridor. Each geographical region now has a working group, which meets monthly with the community and public officials to address problems and discuss solutions. These groups are devoted to strengthening the assets within the city and believe in revitalization over demolition.

The coalition sparked discourse in the Hilltop communities, who began a seven week discussion process, known as the Dialogues-To-Action, after which 125 people gave their recommendations and voted on which issues they should tackle first. They set their sights on reclaiming vacant properties and coordinating social services, with new discussions covering public safety and the police relationship with residents.

From these discussions the Hilltop Alliance was created, which unites the communities of Allentown, Arlington, Arlington Heights, Beltzhoover, Bon Air, Carrick, Knoxville, Mt. Oliver, Mt. Oliver Borough, and St. Clair under one umbrella organization to serve the greater good of the Hilltop. The Alliance stresses the importance of working together, following a national model of Everyday Democracy, which encourages participatory analysis of a community’s needs to address their most persistent problems and find the best strategy to solve them. They work within the ten Hilltop communities to reclaim vacant lots, turn them into affordable housing, and educate members of the community about their rights, available assistance, and education opportunities. Their goal is to maintain and take advantage of the assets already in existence in the Hilltop, so some of its focus is devoted to saving homes by mitigating foreclosures and weatherizing to lower heating costs, allowing people to stay in the Hilltop and live comfortably.

One of their goals is the creation of a One-Stop-Shop. One-quarter of the Hilltop population lives below the poverty line and many residents don’t know how to get needed assistance with finances, utilities and food, or employment. The One-Stop-Shop will be a single location where neighbors could go to learn about and apply for assistance, and search for employment. The Action Team behind the One-Stop-Shop holds monthly meetings and uses grassroots campaigns to get more involvement from the community. Their short term goal is to create and maintain an online directory of available services.

Another notable Pittsburgh CDC is the Bloomfield-Garfield Corporation (BGC). The BGC was formed in 1978 when Reverend Leo Henry, concerned with the deterioration of his beloved neighborhood, gathered his community and urged them to help save Garfield and Bloomfield. That night, he proposed the Bloomfield-Garfield Corporation selling shares to the community for $5 each to gain their involvement. The BGC became official one year later and its efforts since have been all-encompassing.

They have built new houses and renovated old ones, supplying each house with energy efficient appliances and heating to reduce utility costs. This ensures that people can afford to stay in their homes, strengthening the community and making it safer.

The BGC has revitalized the commercial district along Penn Avenue, bringing in art galleries and restaurants. Vegan-friendly eateries like Spak Brothers and The Quiet Storm as well as hip art galleries and music venues like Garfield Artworks and ModernFormations have transformed Garfield into a happening place. The Penn Avenue Arts Initiative, partnering with the BGC, has quickened the effort by creating Unblurred, a monthly gallery crawl along the Penn Avenue corridor. They have also reduced crime by forming a Public Safety Task Force that meets monthly with police officials and citizens to address problems and strategize the best solutions for making the neighborhood safer.

By opening a Youth Development Center, the BGC is also giving area youth a head start. They have created and run over 100 after-school programs that help students graduate, get help with classes online, find internships, and eventually find employment. They have also launched a Youth Employment Program, which helps 17-21 year olds find employment around the region and gain valuable experience. With these programs in place, the BGC is helping to ensure the continued thriving of Garfield, Bloomfield, and Friendship.

The BGC has also partnered with other CDC’s from Bloomfield, Garfield, Friendship, and Lawrenceville to form the Penn Avenue Corridor Phasing Plan Committee (PACPPC). As their name suggests, the PACPPC is responsible for the revitalization of the Penn Avenue Corridor, a project that is slated to start next summer. The Penn Corridor project will improve the deteriorating conditions on Penn Avenue, between 34th Street and Negley Avenue by replacing sidewalks; installing new pedestrian and traffic lights, trees, and benches; and repaving and restructuring the street. The PACPPC has worked closely with the community and developers to pinpoint the community needs and tailor the project to the specific flow of people, cars, and businesses along the corridor. The end result should be a safer, less congested Penn Avenue, which should increase business interest and community pride.

Pittsburgh has come a long way since its smoky industrial days, thanks to the dedication of its people and the CDCs they have formed. Its growing reputation of excellence in energy efficient building and its continued community improvements have started to draw people to the Golden Triangle, and last year Pittsburgh gained residents for the first time in decades. ■